ONE LITTLE TOWN WITH THE GREAT ENGLISH AUTHORS OF THE 20TH CENTURY AS ODD AND CAPTIVATING NEIGHBORS.

WELCOME TO BASSENWOOD.

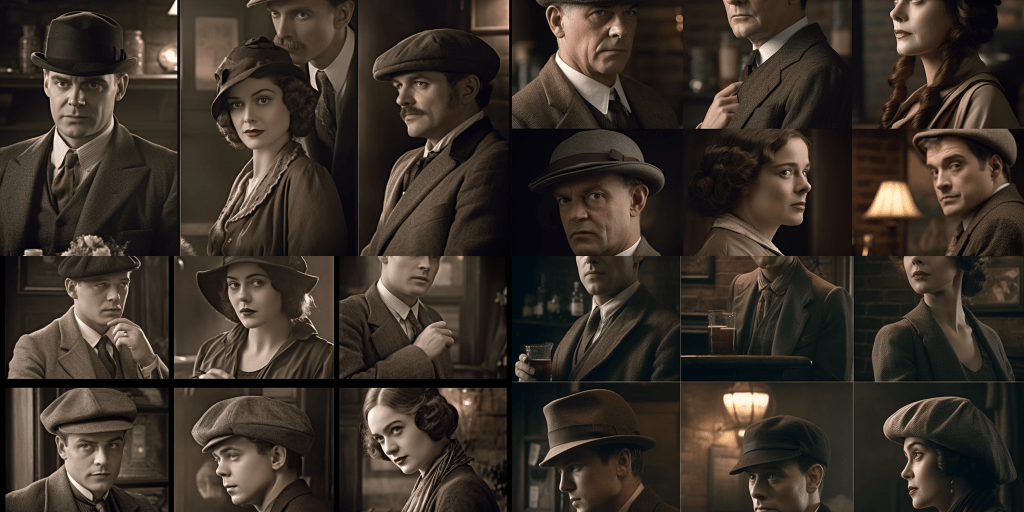

It’s hard to put your finger on why DOWNTON ABBEY was a success. For all the talk of nostalgia, wealth, romance and whatnot, the fact is there are many similar programs that die the death. DOWNTON had that certain something–although my dog Beatrice disagrees in the fullest, promptly leaving the room whenever it would play.

Whatever that something is, BASSENWOOD seems to have it.

It’s not realism in its favor, that’s for sure.

BASSENWOOD is the name of some kind of spot in England not, apparently, hellishly far from London, and small and cozy and alluring like many of those TV-created British villages.

In it, in an unlikely setup, slowly over the years after World War One, a collection of prominent U.K. authors and author-hopefuls gathered to live, after rumors reached them of a perfect sort of climate involving just the essentials and an enviable quietude in the town.

What we have, then, is a great what-if. What if some of the greatest and most eccentric authors of the early 20th Century lived roughly together in the same town?

What if, say, someone very similar to a C.S. Lewis or J.M. Barrie had to put up with the seriousness of a J.R.R. Tolkien type, who, in turn, was challenged by the genius of an Agatha Christie-like detective writer every bit his equal? And could this prematurely-old grandmother figure offer guidance to a young and spritely Beatrix Potter-type of writer? Would the Ian Fleming/Graham Greene spy-story novelist be drawn to her, or stay with his beautiful-if-a-bit-dull wife?

It’s hard to say if the oddness of BASSENWOOD, with its Downton-like ensemble cast, is the key to its public embrace, or if it’s the melancholy mysteriousness that gives off a glow in the way that QUEEN’S GAMBIT did.

The year is 1925.

P.J.D. Sencarrow is a brilliant, distracted academic and a WWI veteran whose relative youth has been sucked away by war experiences his friend James McCandless never really had to go through due to an early bullet injury to his leg. This is only one of their conflicts. The other is that Sencarrow believes fantasy exists to serve a deeper understanding of the seriousness of myth and the ancient world, whereas McCandless writes children’s fiction like Peter Pan, Narnia, and the Wind in the Willows, and thinks it is mere escapism.

They have been joined by the adventure writer Robb Haverton, who is some kind of hodgepodge of Rudyard Kipling, the James Bond creator Ian Fleming, and H. Rider Haggard who wrote Indiana Jones sorts of stories in real life. Haverton is a tough, frequently bored exaggerator who is always in search of some kind of rough drama to get involved in, usually gambling. He agitates the others, but they enjoy his stirring of the pot.

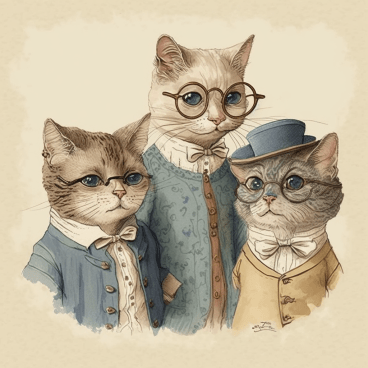

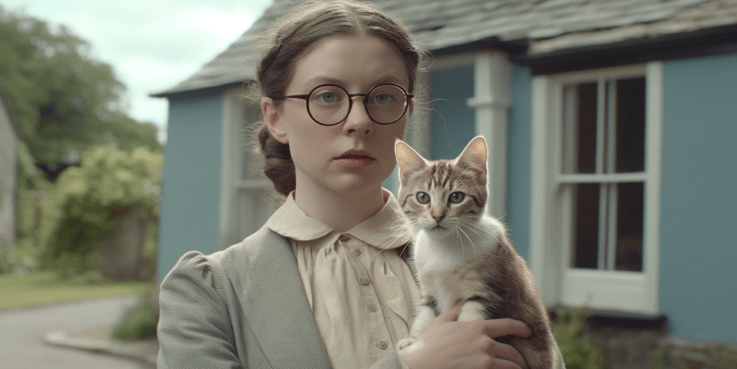

The women of the group include Sarah Peating, the Beatrix Potter type girl who appears young and naiive, silly and charming, but a quick learner with a great business mind, and a welcome reprieve from some of the men’s gloominess. Sarah’s tales of a near-sighted cat family and their “showpeople” rivals, the magician rabbits and the music-minded badgers, become far and away more successful than anyone else’s work, which threatens to sour the friendships.

Her friend, the other major female figure, is the aforementioned crime fiction master Tabitha Marristy, who, in the finale, it turns out, after so many plot developments, may have been arranging and manipulating events with all of the friends since the beginning, simply to amuse herself.

The authors often meet up in the local cafes and pubs–the fact they cannot agree on a single site is part of the fun of their continuing niggling of each other–and their banter is both clever and often deep, a philosophical Algonquin Round Table that nonetheless peppers conversations with references to elves, goblins, lost temples and talking cats.

Each author’s unique–and tonally completely different–universes meld into the mix of friendship and romance.

The Agatha Christie styled mystery has a dizzying array of characters, often a source of amusement.

The Beatrix Potter inspired stories have an adorable collection of near-sighted cats, and neighbors of badgers and “flashy showbusiness” rabbits.

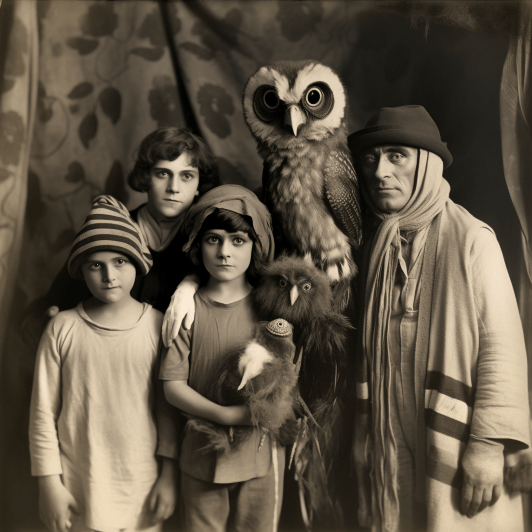

And the other children’s book author, McCandless, favors a more Peter Pan/Narnia kind of world of talking owls and dated East Indian villains who are later pictured in marvelously re-created Arthur Rackham styled illustrations and a West End musical play…

…while here, below, you can taste the grim realities of the Tolkien-like world of Sencarrow:

Or the dark excitements of the adventures Haverton concocts involving temples, treasures, and relics:

Mention has to be made of the incredibly charming and varied techniques of animation that show us different versions of Sarah’s creations. In her dreams, the bespectacled family of cats she draws are presented in amusing stop-motion (or stop-motion inspired? I don’t know much about animation) which brings to life the persnickity near-sighted cat Tottle, but later, the character is frequently sighted by Sarah in daydream-fantasy sequences in which Tottle is more real, more credibly physical (which must be computer generated, I believe). These encounters become more comically improbable as Tottle the cat first appears in traditional explorations of the old-fashioned, Peter Rabbit type character… and then later offers her raunchy advice on a suitor.

Most intriguing is the fact that after awhile, we no longer need to see Sarah daydreaming at all, as Tottle and his rabbit enemy Brannit are seen trodding around the English village all by themselves, having become for us, it seems, independent and deeply serious characters with a life unimagined even by the author herself.

There are also beautiful excursions (as the authors do their writing) into the Peter Pan-type storybook world of Nevertell, where children fly as they are held by ever-present giant owls, and who do battle with East Indian pirates who–despite the author’s reluctance–end up giving everyone a lesson on the end of colonialism and how to proceed as equals. It’s winsome, comical, and exciting.

The medieval Tolkien-like world envisioned by PJD Sencarrow is mostly dark and unpleasant where the court backstabbings somewhat mimic publishing politics, but the glimmers of, you’d have to say, fellowship…are so wonderful you’d really like to see a whole spinoff set in that land completely. It’s a place where little elven people forge things for the warlike races that surround them, but manage to keep their own hamlet free of strife. Instead of a ring of power, the heroes pursue a set of nine Excalibur-like swords with which no army can be defeated.

For his part, the adventurer’s world is almost an excessively grim Indiana Jones reality of Egyptian temples and African jungles in the King Solomon’s Mines tradition. The hero is a womanizer who–also despite its creator’s plans–gets critical lessons in his callousness from women who frequently play the juicy villains.

Maybe it is this fusion of so many popular old genres that makes the BASSENWOOD series work for so many people. It does not work at all for Beatrice, however. She is my constant companion, but when either that show or DOWNTON are on, out the room she goes.

Go figure.

At any rate, this is going to be a good review. Even though BASSENWOOD still has 2 episodes left and has not yet “stuck the landing,” I am willing to say you will be hard pressed to find someone who doesn’t like it. It appeals to Boomers and Zoomers, Brits and Yanks, just about anyone except my dog.

The plot twists promised in the next few episodes are worth speculating about–and you can participate even if you haven’t seen the show…

*Are the mysterious figures lurking about the town of Bassenwood gangsters looking for money Haverton owes, or are they government agents curious about the Communist Russian boyfriend Sarah recently had?

*Will McCandless get involved with the gorgeous provocateur who tried to get his books banned for being “seditious witchcraft secretly meant to undermine the British Empire,” or will he fall for the tamer but highly compatible Judith Meyers, whose Jewish family cannot stand him?

*Is it really possible that Sencarrow really did “borrow” massive parts of his LORD OF THE RINGS-type saga from a Black soldier he served with in WWI as they told stories in the trenches?

Intrigue both inside and outside of the stories…

And of course the stories themselves left us on a cliff, didn’t they? Will Tottle, the near-sighted cat who wants quiet, finally get rid of the noisy badgers hiding at the farm next door–and will that change everything? Will the Mosstook Elves in Sencarrow’s saga end up destroying the swords they worked so hard to retrieve or end up at each other’s throats? And who is killing all the great butlers of Europe, in Tabitha Marristy’s new detective novel?

For me, personally, however, much of the pleasure of the series is paying attention to the basic framework: the friends of Bassenwood have their fortunes rise and fall inversely to each other… as some of the authors see their works gather in appeal and acclaim, others see theirs begin to drop, and how they manage their envy and closeness holds a lot of wisdom for anyone dealing with difficult friendships.

My own most difficult friendship is with Beatrice the bassett hound, as my readers already know. It isn’t the fussiness about her eating, or the messes she generates daily, but rather what I call the intwining. It’s a term I use to describe her ability to get inside my head, weaving her goals into the folds of my brain insidiously. Fact is, it would make a rather good storybook on its own, but I doubt it would win support from a lot of children. Beatrice tends to want me to do things I don’t want to do.

It’s quite aggravating to know that in large part she is right about those she wants me to kill and in large measure that is because people in this town fail to appreciate the little niceties and formalities that make life easier for all. They never seem to notice the simple pleasures a small village like this could bring, either–if people were like they are in stories. And that dullness of mind which persons around here have is probably why they are among the few who cannot appreciate the quiet genius of something like BASSENWOOD and deserve what is coming to them, and why I’m going to enjoy giving it to them.

Let the critics in this town sharpen their knives. I have knives of my own.

Until next time, happy viewing to all!